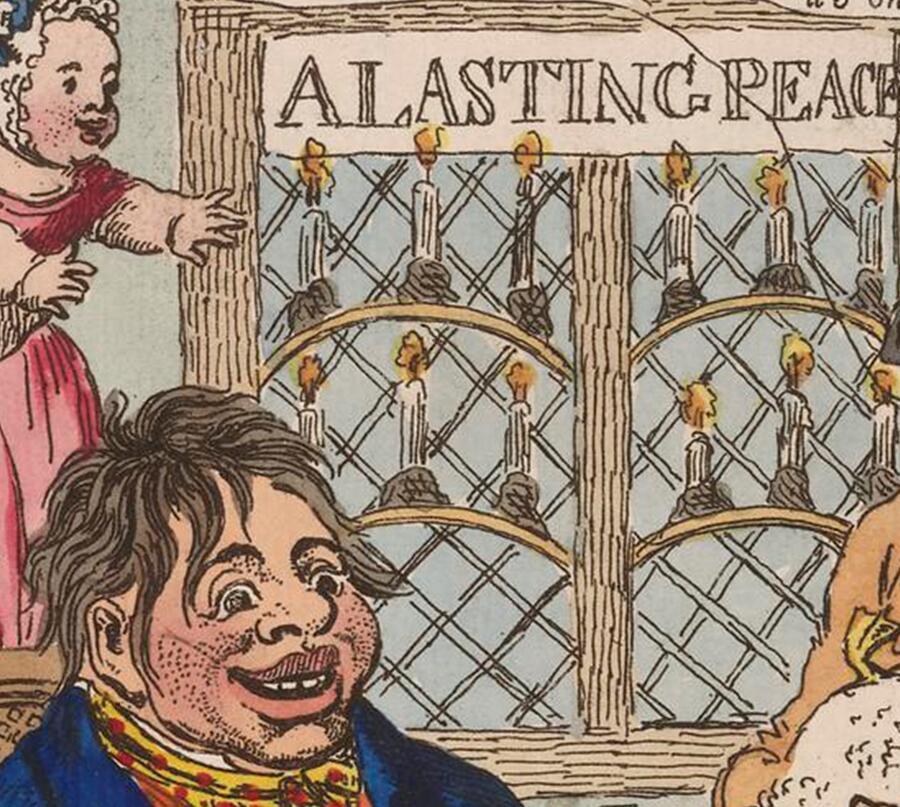

Above: George Cruikshank, The Royal Rushlight, 1821, Courtesy of UCLA, Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts.

This satirical print shows Queen Caroline as a rushlight held in a typical kitchen candlestick.

Candles

Tallow candles made from sheep, cow or pig fat were the most common. They were temperamental, smelly, burned unevenly and the wick had to be trimmed regularly while burning. Candles made from costly beeswax were available only to the very wealthiest and to the church. Candles were taxed from 1709 – 1831.