Sir Richard Westmacott RA (1775 - 1856)

Sir William Chambers

c.1797

SM SC21

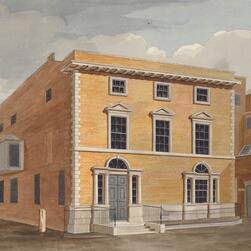

Sir William Chambers (1723 – 1796) was born in Sweden, educated in England, and in his youth journeyed to India and China as a cadet in the Swedish East India Company. From 1749 he studied architecture at Jacques-François Blondel's École des Arts, Paris, then undertook further years of study in Italy. Returning to England in 1755, he became the ‘arch-professional and establishment architect in the England of George III’. A founding member of the Royal Academy, he was architectural tutor to the Prince of Wales, later George III, under whom he rose to become Surveyor-General.

![The casino has been described as ‘the first demonstration in stone of [the] new Franco-Roman wave in Europe’.](https://www.soane.org/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_page/public/gallery/Treatise%201080x1080%20A_0.jpg?itok=yYsXW0eJ)