Denise Scott Brown’s ideas and work as architect, planner, urbanist, theorist, writer and educator have had a global influence on architects for nearly fifty years, transforming thinking about architecture and cities.

She was born in what was then Northern Rhodesia in 1931. She attended the University of Witwatersrand, South Africa, and the Architectural Association, London, before receiving a master’s degree in architecture and city planning from the University of Pennsylvania, beginning a long association with the university and the city of Philadelphia, where she now lives.

As an academic and educator, Scott Brown has led countless research projects, notably Learning from Las Vegas, which became a seminal book (1972; revised edition 1977, with Robert Venturi and Steven Izenour). Both the ideas and the techniques employed in this and other studies have proved highly influential on the subsequent direction of architectural research. Scott Brown’s other books include The View from the Campidoglio (1984 with Robert Venturi), Architecture as Signs and Systems for a Mannerist Time (2004 with Robert Venturi) and Having Words (2009).

As principal of Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates, Scott Brown has been responsible for numerous urban plans and master plans. She has been instrumental in the design of buildings such as the Département de la Haute-Garonne provincial capitol building in Toulouse, France (1999); the Mielparque resort in Kirifuri National Park, Japan (1997); and the Sainsbury Wing of the National Gallery, London (1991), recently awarded Grade 1 listing.

The following short texts have been excerpted from Denise Scott Brown’s Soane Medal Lecture, delivered in 2018.

Learning from Johannesburg Back to top

I have never thought of myself as a photographer, only an architect and urbanist, but for seven decades I have taken photographs and used photography to illustrate the ideas behind what I teach, design and write. These reflect so much of who I am.

I was born in 1931, in ’Nkana in Zambia. In 1933 my parents moved back to Johannesburg which was then less than 50 years old and very much a mining city, and if it had gateways at all these would be its cooling towers and mine dumps. In South Africa I also learned to love so much of its own architecture, like Kwa Zulu huts, made of straw and mud; and the village houses of the Mapoch Ndebele, whose wattle-and-daub structures fused Arab influences from the north, Mapoch traditions of hand-painting patterns from their beadwork on their houses, and a new idea of decorating their entryways with depictions of the fronts of nearby suburban houses. At the same time I was very attracted to the Cape Dutch rural vernacular, like those in the town square in Stellenbosch, and the gabled farmhouse buildings nearby, whose builders are identified by the particularities of their pediments.

Learning from London Back to top

In 1952, I recognised I needed further training and moved to London where I found work with the architect and planner Frederick Gibberd. At the same time I visited the Architectural Association and met people I liked, who encouraged me to apply. As a student there I encountered John Soane, via John Summerson, who was then director of the Soane Museum and an AA lecturer. He taught a course on classicism, with a special focus on Italian and English mannerism and architects like Jones, Wren, Nash, Hawksmoor and Soane himself. Through Summerson I considered ranges of building types and studied buildings within the wider tissue of the town. By combining insights from architectural history, social thought and urbanism, he helped me prepare to be both an architect and a planner. I’ve since used Georgian architecture and Summerson’s slice of the world as a framework to study everything from Soweto, Levittown and American inner-city housing, to Lilong, academic complexes and The Strip. And eventually his interpretations also guided us in designing the National Gallery Sainsbury Wing.

Another touchstone at the time was a reprint of a 1929 lecture by Le Corbusier called ‘If I Had to Teach You Architecture’. In it he encourages students to look at the way a boat docks at a harbour or at the layout of a train kitchen – ie, lovable reflections of 1920s functionalism. If only life were that simple! In the same text Corbu offered another instruction to go behind a building, to where architects consider practicalities rather than aesthetics, and where you can find interesting things. Dutifully, I photographed the backs of buildings on Bond Street and there it all was. The lack of pretension of behind-the-scenes London also seemed to fit with the ideas of Alison and Peter Smithson and the Independent Group, and their version of mannerism as it gravitated around pop art and brutalism.

Learning from Italy Back to top

In July 1956, with my first husband Robert Scott Brown, I packed up and left the Elysian Fields of Georgian London and spent six months in Italy. We set off in our three-wheeled Morgan, accompanied by a bag of spare parts from the Morgan factory. Our destination was a CIAM summer school in Venice and our route was devised by Robin Middleton to cover a maximum of mannerist art and architecture.

In Venice I added further examples to the architecture I loved in South Africa and London: grand palazzos whose frontages followed the age-long design code Summerson had described, but with variations in window arches and widths that indicated Romanesque, Gothic, Renaissance and Baroque eras. When autumn came we drove south, sightseeing in Florence and Sienna and wintering in Rome, photographing roadside signs and symbols on the way, and where we worked for six weeks for Giuseppe Vaccaro. In the New Year we went to Naples, and continued to photograph interesting urban forms.

The linear city was an object of fascination at the time, and was seen to be a logical response to railways and their stops and a means of assuring urban and rural access in cities. Earlier the previous summer, the theme of the CIAM school was planning a future Lagoon City on Mestre, an industrial town on the Venetian mainland, which we took as a chance to design a linear city of our own. Though rejecting rigid CIAM urbanism we proceeded with a Sienna linearity that was not absolute but responded to topography and to where you could walk or grow vegetables. And the donkey? Well, it was the train and in our new era it could go at 100mph! ‘But how would it stop?’ our jury asked. Unbelievably, we announced, ‘That doesn’t matter.’

Learning from Philadelphia Back to top

When we were finishing at the AA, Peter Smithson had asked what Robert and I would do next, and when we told him we wanted to study city planning in America he insisted we go to the University of Pennsylvania, to Louis Kahn, who he had been corresponding with for several years. We took his advice and after Italy enrolled as planning students. We soon discovered that Kahn ran design studios open to architects in architecture not in planning: ‘Sociologists believe in 2.5 people’, he argued, ‘how can you believe in them?’ We tried to switch, but then discovered that we actually liked the planners – among them a new generation of social scientists who were advance guards of the New Left, and who endorsed ‘advocacy planning’, where you find out what the people you are designing for really want, rather than imposing architects’ oughts on them.

A short while later, in 1959, Robert was killed in a car accident. I went home, but my family and teachers at Penn all said ‘finish what you so loved doing'’ Sorrowing deeply, I continued my studies, and soon found richness beyond architecture in land economics, regional science and the systems planning that went with them. And as my interests widened, I found more reason than ever to photograph, not least because I was doing so to teach. I was also drawn to Philadelphia street life, its colours and architecture, and the dangers of crossing the road. At the same time, I explored the housing stock in neighbourhoods rich and poor. Philadelphia colonial townhouses were Georgian but built of bricks more finely wrought than the London yellow stocks – though I love these just the same.

I met Bob Venturi at a faculty meeting at Penn. Architectural preservation brought us together. At one of our weekly meetings the scheduled demolition of the former university library building was on the agenda. I was shocked to discover that most of my colleagues wanted it torn down. I offered a case for the defence, and this argument prevailed. After that the young architect who had heard our New City presentation with Kahn came up and said, ‘My name’s Robert Venturi. I agree with everything you said.’ I think I shouted at him, ‘Then why didn’t you say anything!’ In 1968 Bob and I moved from the second floor of the Vanna Venturi House, into a 24th-floor apartment in the Society Hill Towers designed by I M Pei. From this domestic version of an airplane window I could observe all of colonial Philadelphia below, as well as spot planes landing at the airport, watch over whole districts and weather systems and see individual snowflakes driving towards me. Armed with these aerial views, in my first-year teaching studio I set projects that sent students into Philadelphia. Architects often talk about designing public space but I wanted them to learn, before designing, how people actually use such spaces, and to listen when social planners warn that it isn’t public unless the public uses it.

Learning from Las Vegas Back to top

In 1965 I grew my ideas further, at Berkeley then UCLA, where I was hired to help start a new architecture school. We spent our first year preparing and I continued photographing. My own research and my plans for studios at UCLA followed the advice of Penn planners – go where people go. In California this meant the highway or the beach. We explored both.

From Berkeley, I had visited Las Vegas, initiated my western auto-city collection and returned there several times in the next year. Then Bob and I were given teaching appointments at Yale, I proposed a new studio, wrote its work papers and suggested its name, Learning from Las Vegas. What we hoped to learn was not just its system of signs and symbols, but also how 1960s auto-cities worked and why people liked this one so much.

Driving The Strip for the first time I knew it was important, even profound. I also felt that it was ideally suited to take on the philosophies and methods I had derived from planning, and the architectural theories I continued to develop on a mannerist base. What I didn’t know, but hoped, was how much fun it would be, because Bob and I had a great time with our Yale students, analysing and documenting the city in a million different ways – through drawings, sketches, leporellos, stills and films, and through studies of its hotels, casinos, wedding chapels, gas stations, parking lots and signs, and in polemical provocations about its monumentalism and in all of its ducks and decorated sheds.

We even went behind, to those fantastically interesting spaces at the backs of the billboards and casinos. And back yet further, in the open desert that was then behind the casinos, I staged the famous portrait of Bob. I should also say that this was not how Bob normally dressed, but that morning we had been to a city agency asking for funding for our research and Bob wore his most serious suit. He had also spoken to a reporter, which produced a headline in the local paper, ‘Yale Professor Will Praise Strip for $9,000’. In the end, we secured free room and board for everyone at the Stardust Hotel and Howard Hughes lent us his helicopter for an hour.

After I took the photographs of Bob, he took my portrait – not as a faceless person aligned with other monuments but as a woman staring back at the camera. Today, when I look at this image and myself then, confidently standing there, hands on hips, I see someone who is happy with her professional life and happier still with her personal life. I also see someone who is feeling triumphant and daring anyone to say otherwise. But irony is there too, for in my mind was a poem, ‘I am monarch of all I survey’, and I was also spoofing Robert Moses.

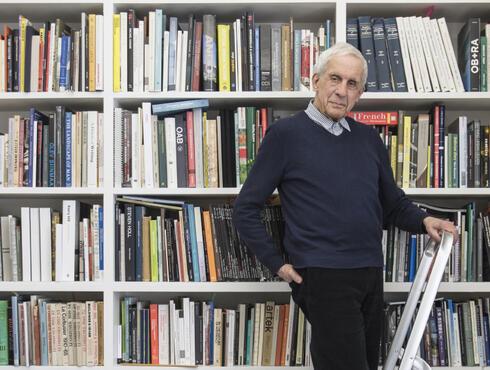

Header image credit: Photo Denise Scott Brown © the architect