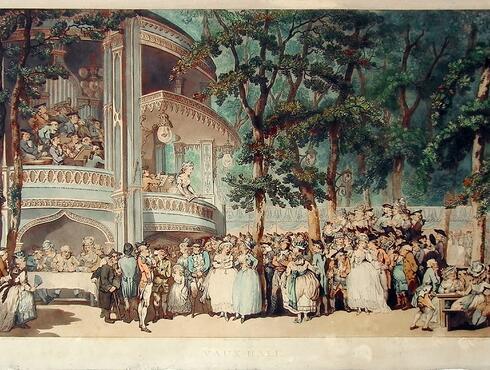

John Babington and Pyrotechnia

Ralph Mab, printed by John Droeshout

Engraved titlepage to John Babington, Pyrotechnia, Or a Discourse of Artificiall Fire workes for Pleasure

Engraving on paper

1635

The British Museum

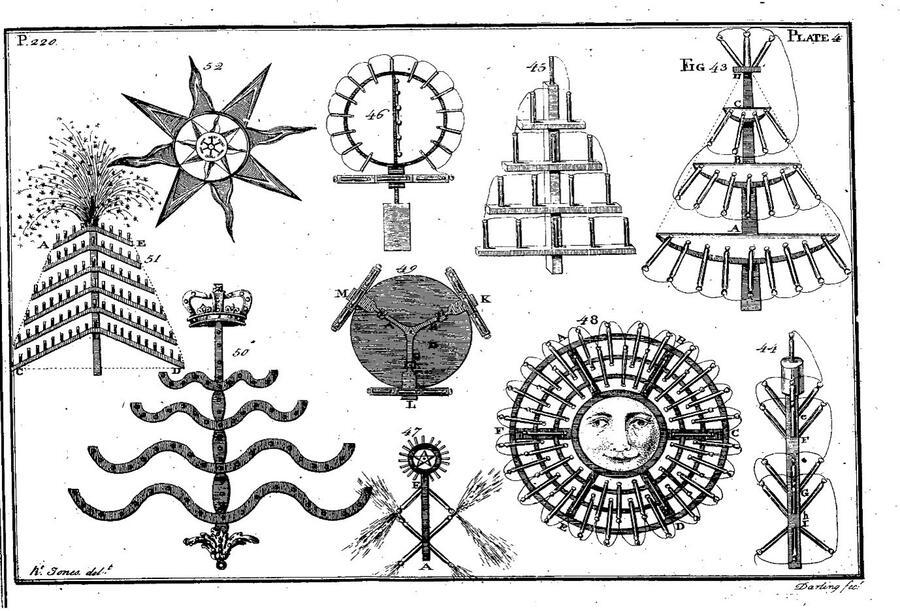

Artillery has been used in England since the fourteenth century. Artillerymen or ‘gunners’ maintained and operated large gunpowder weapons like cannons. The first English manual on fireworks was published by the gunner John Babington in 1635. Pyrotechnia belongs to a wider genre of ‘books of secrets’, which consolidated early scientific knowledge. Pictured here on the title page, Babington asserts his technical, mathematical and cosmological expertise. He is surrounded by designs for elaborate pyrotechnic mechanisms. The globe to his left is an armillary sphere, used to track the movement of heavenly bodies. In periods of peace, it was advantageous for gunners like Babington to raise the status of pyrotechnic knowledge, in order to gain commissions from wealthy patrons. However, the dual purpose of pyrotechnics was never lost on gunners, as Babington explains in the dedication… ‘They may seem to serve only for delight… yet (knowledge of pyrotechnics) may excite and stir up in an ingenious mind, sundry inventions more serviceable in times of war.’